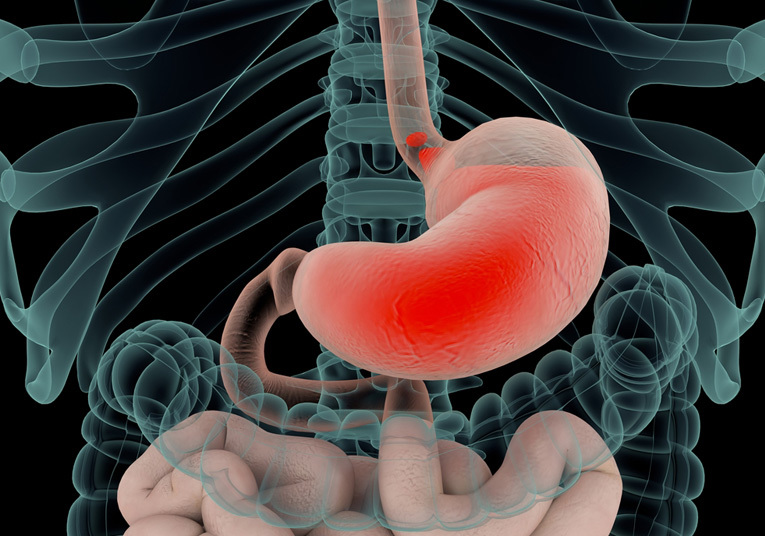

How heartburn and GERD occur

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when stomach acid frequently flows back into the tube connecting your mouth and stomach (esophagus). This backwash (acid reflux) can irritate the lining of your esophagus.

Many people experience acid reflux from time to time. GERD is mild acid reflux that occurs at least twice a week, or moderate to severe acid reflux that occurs at least once a week.

Most people can manage the discomfort of GERD with lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications. But some people with GERD may need stronger medications or surgery to ease symptoms.

Symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of GERD include:

- A burning sensation in your chest (heartburn), usually after eating, which might be worse at night

- Chest pain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Regurgitation of food or sour liquid

- Sensation of a lump in your throat

If you have nighttime acid reflux, you might also experience:

- Chronic cough

- Laryngitis

- New or worsening asthma

- Disrupted sleep

When to see a doctor

Seek immediate medical care if you have chest pain, especially if you also have shortness of breath, or jaw or arm pain. These may be signs and symptoms of a heart attack.

Make an appointment with your doctor if you:

- Experience severe or frequent GERD symptoms

- Take over-the-counter medications for heartburn more than twice a week

Causes

GERD is caused by frequent acid reflux.

When you swallow, a circular band of muscle around the bottom of your esophagus (lower esophageal sphincter) relaxes to allow food and liquid to flow into your stomach. Then the sphincter closes again.

If the sphincter relaxes abnormally or weakens, stomach acid can flow back up into your esophagus. This constant backwash of acid irritates the lining of your esophagus, often causing it to become inflamed.

Risk factors

Conditions that can increase your risk of GERD include:

- Obesity

- Bulging of the top of the stomach up into the diaphragm (hiatal hernia)

- Pregnancy

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma

- Delayed stomach emptying

Factors that can aggravate acid reflux include:

- Smoking

- Eating large meals or eating late at night

- Eating certain foods (triggers) such as fatty or fried foods

- Drinking certain beverages, such as alcohol or coffee

- Taking certain medications, such as aspirin

Complications

Over time, chronic inflammation in your esophagus can cause:

- Narrowing of the esophagus (esophageal stricture).Damage to the lower esophagus from stomach acid causes scar tissue to form. The scar tissue narrows the food pathway, leading to problems with swallowing.

- An open sore in the esophagus (esophageal ulcer).Stomach acid can wear away tissue in the esophagus, causing an open sore to form. An esophageal ulcer can bleed, cause pain and make swallowing difficult.

- Precancerous changes to the esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus).Damage from acid can cause changes in the tissue lining the lower esophagus. These changes Diagnosis

Endoscopy

Your doctor might be able to diagnose GERD based on a physical examination and history of your signs and symptoms.

To confirm a diagnosis of GERD, or to check for complications, your doctor might recommend:

- Upper endoscopy. Your doctor inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera (endoscope) down your throat, to examine the inside of your esophagus and stomach. Test results can often be normal when reflux is present, but an endoscopy may detect inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) or other complications. An endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications such as Barrett’s esophagus.

- Ambulatory acid (pH) probe test. A monitor is placed in your esophagus to identify when, and for how long, stomach acid regurgitates there. The monitor connects to a small computer that you wear around your waist or with a strap over your shoulder. The monitor might be a thin, flexible tube (catheter) that’s threaded through your nose into your esophagus, or a clip that’s placed in your esophagus during an endoscopy and that gets passed into your stool after about two days.

- Esophageal manometry. This test measures the rhythmic muscle contractions in your esophagus when you swallow. Esophageal manometry also measures the coordination and force exerted by the muscles of your esophagus.

- X-ray of your upper digestive system. X-rays are taken after you drink a chalky liquid that coats and fills the inside lining of your digestive tract. The coating allows your doctor to see a silhouette of your esophagus, stomach and upper intestine. You may also be asked to swallow a barium pill that can help diagnose a narrowing of the esophagus that may interfere with swallowing.

Treatment

GERD surgery

Substitute for esophageal sphincter

Your doctor is likely to recommend that you first try lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications. If you don’t experience relief within a few weeks, your doctor might recommend prescription medication or surgery.

Over-the-counter medications

The options include:

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, such as Mylanta, Rolaids and Tums, may provide quick relief. But antacids alone won’t heal an inflamed esophagus damaged by stomach acid. Overuse of some antacids can cause side effects, such as diarrhea or sometimes kidney problems.

- Medications to reduce acid production. These medications — known as H-2-receptor blockers — include cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR) and ranitidine (Zantac). H-2-receptor blockers don’t act as quickly as antacids, but they provide longer relief and may decrease acid production from the stomach for up to 12 hours. Stronger versions are available by prescription.

- Medications that block acid production and heal the esophagus. These medications — known as proton pump inhibitors — are stronger acid blockers than H-2-receptor blockers and allow time for damaged esophageal tissue to heal. Over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole (Prevacid 24 HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC, Zegerid OTC).

Prescription medications

Prescription-strength treatments for GERD include:

- Prescription-strength H-2-receptor blockers. These include prescription-strength famotidine (Pepcid), nizatidine and ranitidine (Zantac). These medications are generally well-tolerated but long-term use may be associated with a slight increase in risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency and bone fractures.

- Prescription-strength proton pump inhibitors. These include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). Although generally well-tolerated, these medications might cause diarrhea, headache, nausea and vitamin B-12 deficiency. Chronic use might increase the risk of hip fracture.

- Medication to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter. Baclofen may ease GERD by decreasing the frequency of relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter. Side effects might include fatigue or nausea.

Surgery and other procedures

GERD can usually be controlled with medication. But if medications don’t help or you wish to avoid long-term medication use, your doctor might recommend:

- The surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the lower esophageal sphincter, to tighten the muscle and prevent reflux. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure. The wrapping of the top part of the stomach can be partial or complete.

- LINX device.A ring of tiny magnetic beads is wrapped around the junction of the stomach and esophagus. The magnetic attraction between the beads is strong enough to keep the junction closed to refluxing acid, but weak enough to allow food to pass through. The Linx device can be implanted using minimally invasive surgery.